Often the key to writing good code is not having a mastery of whatever programming language you are using, but in using mathematical tricks to express whatever your doing in a way that has an easy solution. I thought I would write up one of my struggles trying to make one of the key function in SoupX more efficient. I’m sure there’s a solution to the same problem hiding somewhere on the internet, but I couldn’t find it so perhaps it will be useful to someone else.

The problem I needed to solve was as follows. I had $x$ “units” to allocate to $N$ categories or “buckets”, where each bucket has a maximum capacity that cannot be exceeded and the buckets are weighted so that more of our “stuff to allocate” goes to some buckets. That is, we have $x$ counts to split between $N$ buckets, where each bucket has a weight $w_i$ and maximum capacity $y_i$.

This seems pretty esoteric, but I care about it for a practical reason. At a certain point I know that $x$ counts in a cell are contamination and that in the background, each gene $g$ is expressed at a certain level $b_g$ (the weights $w_i$) and that we observe $n_g$ counts for each gene. Obviously we can’t remove more counts than we observe, so the observed counts form our maximum bucket size $y_i$

The brute force solution

When I force wrote the relevant function, I didn’t really think about it too much and just did the first thing I was confident worked. This is to allocate counts according to the weights, ignoring the maximas $y_i$, then re-allocate whatever exceeded the limits until there was nothing (or very little) to reallocate. Something like this

set.seed(1137)

#Define number of things to distribute, weights and bucket limits

N = 10

x = round(N*.8)

#Weights

ws = abs(rnorm(N))

ws = ws/sum(ws)

#Limits

tops = round(runif(N)*3)

#Tollerance for convergence

tol = 1e-3

out = x*ws

while(sum(ifelse(out>tops,out-tops,rep(0,N)))>tol){

#Harvest excess and re-allocate

w = which(out>tops)

toAdd = sum(out[w]-tops[w])

out[w] = tops[w]

out = out + toAdd*ws

}

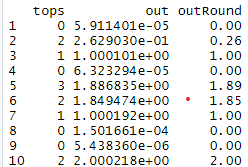

dd = data.frame(tops,out,outRound=round(out,2))

As you can see from the output and the code, this is a pretty dumb method. It can exceed each buckets maximum by an amount less than the variable “tol” and requires potentially many iterations to converge. But it’s easy to understand and gives something close enough to the right answer.

Improving brute force

The problem with starting with the most obvious thing, is that it’s then easy to see how to incrementally improve on that to make things faster. When thinking about the problem properly could yield a completely different approach orders of magnitude faster. Such is the case here.

There are a number of ways we could make the above code faster and more accurate. To start with, there is no need to keep adding to buckets once they’re full. We can also re-normalise the weights to exclude buckets filled in previous iterations. Things with either zero weight or a bucket limit of 0 need not be considered at all. These things do make the code a lot faster, but come with the cost of greater complexity. In the SoupX code, I went very far down this road, including optimising the routine to take advantage of the way sparse matricies are stored. Which made the code usably fast, but very hard to understand what was going on. In fact, I recently discovered that in performing such optimisations, I managed to introduce a bug where bucket weights weren’t properly respected in some cases.

Rethinking the problem

SoupX has been used more and more lately, both by myself and others. The speed of execution was making certain debugging tasks frustratingly slow. So I thought it was worth my time to have another think about this problem, which is by far the slowest part of the code.

After a bit of reflection, I realised that the key question is when counts are correctly allocated, which buckets are full and which are not. Once you know this, you can just set the full buckets to their maximum value and distribute the remaining counts between the buckets that are not full in accordance with their weights (re-normalised to exclude full buckets).

But how can we know which buckets are full or not at the end? The key thing to realise is that the order in which buckets fill up as you increase the number of units allocated can be predicted in advance. Specifically, the buckets with the lowest value of $y_i/w_i$ fill first. This is easy to see why in the case where all weights are equal, then the bucket that fills first is the one with the lowest limit. So the first thing to do is order our buckets by $y_i/w_i$, a very fast operation.

The next trick is to calculate how many counts have been allocated at the exact point where each bucket fills up. For the first bucket this is easy, it is full when $k_0=y_0/w_0$ counts have been allocated. The final trick is to work out how many units are allocated, $k$, when subsequent buckets are full. If we only needed to allocate $k_0 + \epsilon$, where $\epsilon$ is small, then we have already worked out what to do. Just distribute the extra $\epsilon$ counts between all buckets except bucket $0$, with re-normalised weights $w’_i = \frac{w_i}{1-w_0}$. So the next bucket will fill up when $k_1 = \frac{y_1}{w’_1} + y_0$ counts have been distributed.

Taking this to its logical conclusion, the number of counts allocated when bucket $i$ is filled up (assuming buckets are ordered by $\frac{y_i}{w_i}$) is,

\[k_i = \frac{y_i}{w_i} (1-\sum_{j=0}^{i-1} w_j) + \sum_{j=0}^{i-1} y_j\]This formula is fast and easy to calculate. All that is left to do is find the largest value of $k_i$ less than $x$. We have then identified which buckets will be filled and which will remain unfilled and can allocate everything correctly without any loops. The exact code can be found here. Applying it to the example above,

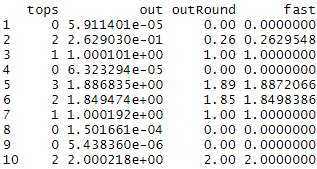

dd$fast = SoupX:::alloc(x,tops,ws)

As you can see, it agrees with the slow loop filled method.

I’m sure if I’d known the right thing to google, there would have been a nice solution to this somewhere on the internet. But I wasn’t able to at the time. This simple improvement makes the code 10-20 times faster. The conceptual simplicity also makes it much less likely to contain a bug.