I recently happened across this paper, which I found quite astonishing. Firstly, it’s written by the 23andMe research team. If there’s still anyone in need of convincing that important and exciting research happens in industry, they should read this paper, because it is high quality and the data they have to draw on are amazing.

But what really struck me was the astonishingly high rate of uniparental disomy they find in the general population, of 1 in 2000. That might seem like a very narrow thing to get excited about, but I hope to convince you why I think it is surprising and that the observation has broad implications.

One of my main research interests is copy number changes, where large areas of DNA are gained or lost, and their consequences. Copy number changes are fascinating for many reasons and are really very poorly understood compared to single nucleotide changes to DNA. Unlike point mutations, we don’t even have a good idea how often copy number changes occur in normal cells. Copy number changes are rare in normal tissues, but that could either be because they only occur rarely, or because they are strongly negatively selected for (i.e., they occur, but kill the cell in the process).

Previously I’d been of the loosely held opinion that copy number changes were probably quite rare. Sure there had been some single cell DNA sequencing papers suggesting high rates of copy number changes, but they have been plagued by technical limitations that make it hard to take as definitive evidence. Thinking about this paper has changed my mind. Let me explain why.

Uniparental disomy

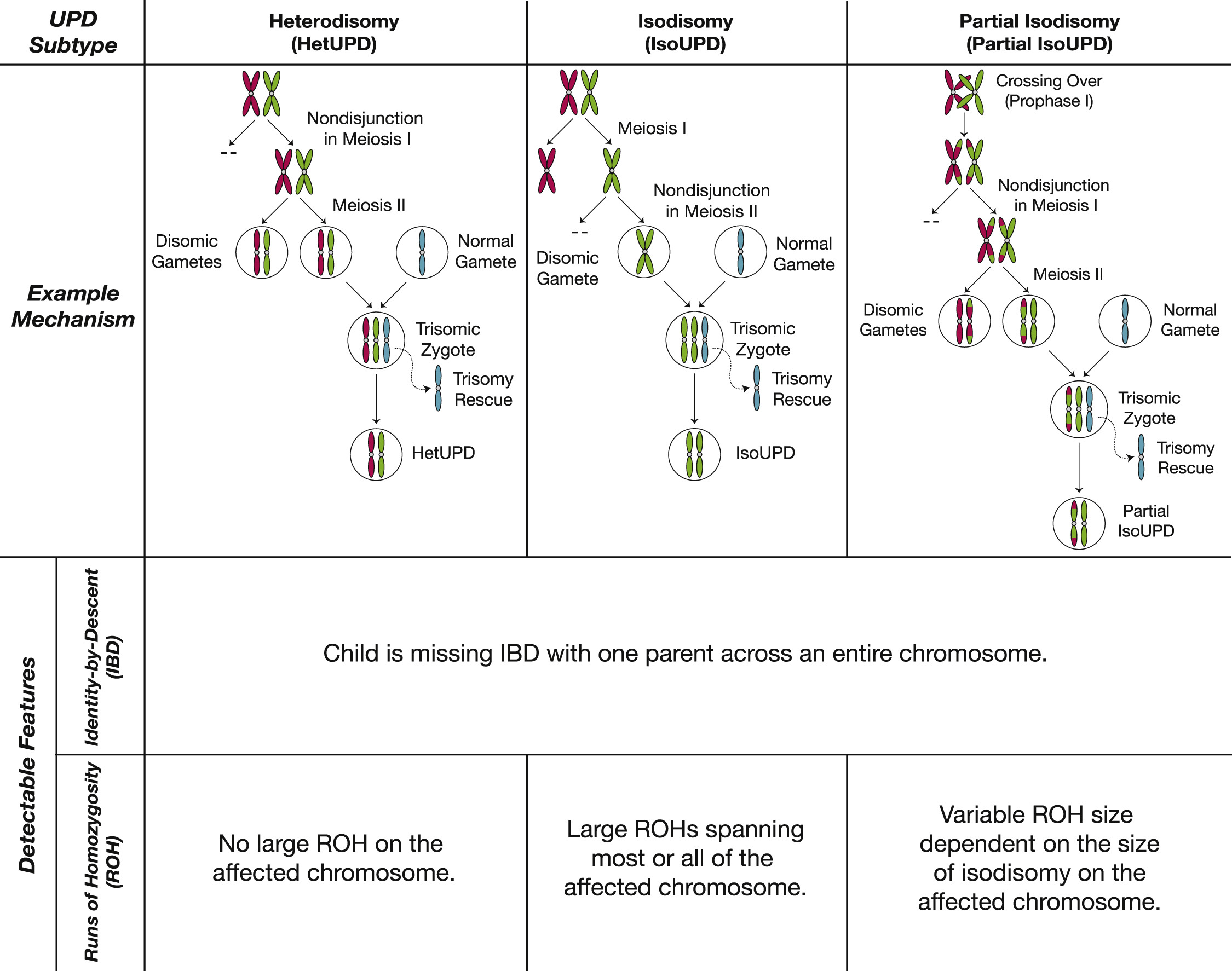

First let’s start with what this paper is measuring, uniparental disomy. Normally, we are born with two copies of each chromosomes, one copy from each of our parents. Individuals with uniparental disomy still have two copies of each chromosome (the ‘disomy’ bit), but due to a reproductive error, one of these chromosome pairs is entirely from one parent (the ‘uniparental’ bit), with the other parent contributing nothing.

What I find interesting about this is what needs to happen in order for it to occur. First, one of the parents has to contribute two copies of a chromosome instead of one. Usually this would combine with the one copy from the other parent and result in trisomy of the effected chromosome. Trisomy is either lethal to the embryo or gives rise to syndromes such as Down’s syndrome (driven by trisomy 21). But what happens in individuals with uniparental disomy is that very early in development, another error in cell division occurs, which causes the daughter cell to inherit 2 copies instead of 3, thereby reversing the trisomy and leading to a viable embryo. This process of reverting a trisomic cell to a disomic one is know as “trisomic rescue”. Some of the time, this second error that “rescues” the trisomy will happen to discard the copy from the parent that only contributed one to begin with, leaving two copies from the same parent. Figure 1 from the paper gives a good summary of this, including the mechanisms that lead to the trisomy in the first place, which are usually maternal.

It is really astonishing that we can detect this and quantify how often it occurs in a population. Beyond it just being amazing, my interest in this observation is what needs to have happened for it to occur. Specifically,

- A trisomy needs to occur, due to meiotic error (i.e., an error in an egg or sperm, usually an egg).

- Post-fertilization, an error has to occur during cell division that changes the chromosome number.

- This error has to effect the exact same chromosome that previously had a trisomy.

- The error needs to happen to segregate out the 2 copies from one parent and discard the 1 copy from the other.

- This error has to happen early enough in development that the corrected cell goes on to form the embryo and the other cells are lost or form extraembryonic tissues.

If we put some numbers to these things, then we can directly connect the rate of uniparental disomy in the population, with the rate at which mitotic errors give rise to copy number changes! Specifically, what we can constrain is the rate of mitotic nondisjunction, that is, how often do chromosomes fail to separate during cell division giving rise to daughter cells with one extra and one fewer copy of the effected chromosome.

Estimating constraints

To do this, we need to put constraints on how often each of the sequence of events outlined above leading to uniparental disomy is to occur. Throughout I will err on the side of taking the estimate that will result in a lower rate of copy number changes per cell division.

The first criteria is that the fertilised egg needs to contain a trisomy. So how often does this happen? Let’s assume that all first trimester miscarriages are driven by trisomies. The first trimester miscarriage rate is about 20%, so let’s take 20% as our trisomy rate.

For this trisomy to be turned into a disomy, we need for the cell division error to hit the same chromosome. If we assume all chromosomes are equally likely to be disrupted in a nondisjunction event, the probability of this happening will be 1/23. It may be that nondisjunction is more likely for a triploid chromosome, so let’s reduce this to 1/10, which is equivalent to the trisomic chrosomoe being about 2.5 times more likely to be disrupted than any other.

In order for the nondisjunction event to lead to detectable uniparental disomy, it needs to be the non-duplicated chromosome that is lost. That is, if the chromosome copy number state was MMP (two maternal, one paternal) before the error, then it must be the paternal copy (P) that is lost. The loss of either copy of (M) will be indistinguishable from a normal individual where no trisomy was ever present. I can’t think of a reason why the loss of P will be more likely than the loss of M, so let’s say that only 1/3 nondisjunctions leads to the MM configuration and detectable uniparental disomy.

The final process we need to constrain is when the trisomic rescue must occur. This needs to happen early enough that the corrected cell displaces any remaining trisomic cells and the embryo consists only of the descendants of the “fixed up” version of the cell with uniparental disomy. So the question becomes, how late (i.e., when the embryo is N cells large) can the rescue occur? It’s hard to see how any cell division after the blastocyst stage, which is around 128 cells, could satisfy this property. It seems more likely that the rescuing nondisjunction should happen in the first few cell divisions, before the embryo reaches the morula or 16 cells. This is the part of the calculation with the most uncertainty to my mind.

Doing the maths

Putting this all together, we need to work out two numbers, given $n$ fertilizations, how many live births do we have and how many live births with uniparental disomy. The number with uniparental disomy is given by, \(n_{upd} = n t x h s\) where

- $t$ is the trisomy rate (which we set to 20%),

- $h$ is the rate at which nondisjunctions hit the altered chromosome (that we set to 1/10),

- $s$ is the rate at which nondisjunctions of the altered chromosome remove the non-duplicated copy resulting in uniparental disomy (which we set to 1/3),

- $x$ is the rate at which a nondisjunction occurs in the first $N$ cells of the embryo: \(x = 1-(1-r)^N \sim 1-(1-r*N) = r*N\) where $r$ is the nondisjunction rate per cell division (the thing we want to know) and the approximation is valid when $r$ is small.

We approximate the number of live births as, \(n_{tot} = n (1-t) + n t x hs\)

So the observed rate of uniparental disomy, $u$, is just the number of uniparental disomic embryos as a fraction of all live births \(u = \frac{txhs}{(1-t)+txhs}\)

Rearranging this and solving for the nondisjunction rate per cell division gives \(r = \frac{u}{1-u} \frac{1-t}{t} \frac{1}{h} \frac{1}{s} \frac{1}{N}\)

Mitotic nondisjunction estimate

I promised that I’d explain why the observed rate of uniparental was surprisingly high. So far I’ve done a bunch of rough calculations and some basic algebra. Just stated the conclusion of the paper, that 1 in 2000 people in the general population have uniparental disomy, probably didn’t strike you as impressively high. But with the above formula we can translate that into a constraint on the mitotic nondisjunction rate. So let’s do that. Given $u=1/2000$, $t=0.2$, $h=1/10$, $s=1/3$, and $N=16$ we get $r \approx 1/267$!

This implies roughly 1 in 300 cell divisions leads to non-disjunction and the gain/loss of a chromosome! This is a really extreme rate, which if true at the level of the organism would lead to copy number changes occurring everywhere. But perhaps we’ve been too permissive in our estimation. There’s not much room to tweak $t$, $h$, or $s$. If anything, we’ve already been pretty permissive in assuming that nondisjunction events are 2.5 times more likely to hit the trisomic chromosome than any other. The biggest uncertainty is in how late the rescue can occur and still give rise to a purely diploid embryo. Let’s say that it’s enough that any of the first 128 cells is “fixed” and set $N=128$. This would then imply a mitotic nondisjunction rate of $\sim 1/2000$. While this is definitely lower than the earlier estimate, 1 in 2000 cell divisions giving rise to a copy number gain or loss is still an astonishingly high rate for an organism comprised of 30 trillion cells.

Conclusion

For someone with a background in astronomy, this whole estimation feels uncomfortably close to the drake equation. For those who don’t know what this is and can’t be bothered clicking the link, it’s a probabilistic estimate of the number of intelligent civilisations we’d expect to observe given different parameter values like the fraction of planets that have life. This comparison is uncomfortable as this equation is widely considered useless because the values of the parameters in the equation are so poorly constrained that you can get just about any answer you want out of it with plausible parameter values.

So can we get just about any answer we want out of the equation for $r$? The range of values for $u$ and $t$ are experimentally and observationally pretty tightly constrained; we can’t plausibly claim that 80% of fertilizations result in trisomies. $h$ and $s$ are less certain, but have to fall in a pretty narrow band $1 < 1/h < 23$ and $1 < 1/s < 3$. Furthermore, using values too far away from $h = 1/23$ and $s=1/3$ would require convincing experimental evidence that there is a strong bias for nondisjunction to hit trisomic chromosomes and non-duplicated copies respectively. So really, the only parameter that is not that well constrained is $N$, how soon in embryo development does the trisomic rescue need to occur to displace the trisomic lineage entirely. Even here, I don’t think things are as ill constrained as they appear. The fact that we see individuals mosaic for trisomy 21 (and other trisomies) suggests that rescue at even the $N=16$ stage does not guarantee that the trisomic lineage will be displaced. Given this, $N=128$ is already stretching plausibility and values higher than that would again require some striking evidence.

In my opinion, the biggest limitation of this approach is that the mitotic nondisjunction rate in early embryogenesis may be very different to the mitotic nondisjunction rate in mature tissues. There is evidence that point mutations occur more frequently in the first few cell divisions than in mature tissues, suggesting this stage of life is more mutagenic. This stage of development is highly also unusual as the paternal genome is being activated and the molecular machinery of the cell established. Given this, it may well be that the first few cell divisions are prone to nondisjunction in a way that more mature cells are not. Nevertheless, the evidence is convincing enough that my new loosely held opinion is that copy number changes probably happen all the time, but are mostly not observed because they are strongly selected against.